- Home

- Gred Herren

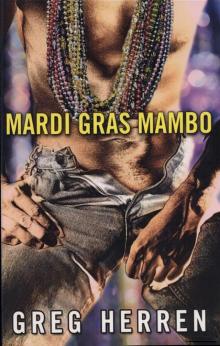

Mardi Gras Mambo Page 14

Mardi Gras Mambo Read online

Page 14

“I’m at Mom and Dad’s. You need to grab Frank and get down here.” I hung up the phone and shoved it back into my bag. “Now, what the hell is going on around here?”

“Don’t kill me!” Misha begged.

“What are you talking about?” I felt really tired. I sank down into a chair and looked at Mom and Dad. “Do you have any idea what’s going on around here?”

Dad took a hit from the bong and blew the smoke out. “Sasha, this is our youngest son, Scotty. He’s not going to hurt you.”

Sasha?

“Wait a minute—hold on for one damn minute.” I held up my hands. “Sasha? I thought Sasha was dead.”

“Because you kill him,” Sasha said, his jaw set, his eyes glaring.

Whoa. “Look, bud, I didn’t kill anyone.”

“Sasha, Scotty didn’t kill anyone,” Mom said, her eyes flashing. “That’s just not possible. You’re mistaken.”

“I saw him,” Sasha insisted.

“Wait a minute.” My head was starting to hurt. “I am fucking confused here. If Sasha is alive, who the hell was killed last night?”

“My brother Pasha.” Sasha was still glaring at me. “And you killed him.”

Pasha? What the hell?

“Stop saying that! I didn’t kill anyone.”

Sasha looked at my mother. “Cecile, I call Pasha last night. He tell me Scotty there. He wearing Zorro costume—cape, tights, mask. Then when I came back to the house, I see man in same costume leave house. I go inside and find Pasha—dead.” He pointed at me again, his hand shaking. “Because you kill him!”

I sighed. “Yes, I was wearing a Zorro costume last night. But I didn’t kill . . . Pasha?” My head felt like it was going to explode. “Who the hell is Pasha?”

“There were lots of men out last night dressed like Zorro, Sasha,” Dad said. “I saw quite a few of them. It’s not like it’s a really original costume or anything.”

Sasha looked at my parents, and then back at me. “Maybe,” he said slowly.

“Yeah,” Mom chimed in. “There’re always lots of Zorros.” She looked at me. “That wasn’t very original, Scotty.” Her tone indicated disappointment, and the look on her face clearly was saying, Didn’t we teach you to be more original with your costuming than that?

“I wasn’t trying to be original; I was trying to be sexy,” I said, through gritted teeth. “Now, will someone please tell me who the hell Pasha is?”

“Pasha my brother,” Sasha said, seeming to relax a little bit. He peered at me. “Maybe not Scotty after all.” He didn’t seem completely convinced, but at least he wasn’t calling me a murderer anymore. That seemed to be a step in the right direction.

“Hey, everyone!” Colin walked in, looking a little the worse for wear. His gold body paint had streaks in it, and his trunks had slipped down a bit, revealing a line of white skin and some pubic hair. He stared at Sasha. “Misha?”

“Sasha.” He thumped his chest. “Me Sasha.”

Colin stared at me. “Scotty, what the—”

“I have no fucking idea.” I waved my hand. “Where’s Frank?”

Colin grinned. “Um, he left with this hot guy from San Diego. I think he’s staying at the Place d’Armes.”

“What?” I felt a pang of jealousy. Sure, we’d always agreed that we didn’t all have to be faithful to each other, but this was the first time any of us had strayed, and Frank was the last one of us I would have expected this from. Then I got over myself. Frank looked great; he was a sexy guy, and I’d dressed us all up in skimpy, sexy costumes. It was a wonder it hadn’t happened last night.

But I still didn’t like it—and I didn’t like that feeling. It said something about me I wasn’t sure I liked very much.

“He’ll be home in the morning.” Colin winked at me.

I let it go. I’d deal with it later. “Back to the subject at hand, will someone please explain to me who the hell Pasha was?”

“Scotty”—Mom took a hit off the bong—“there were three of them. Identical triplets.”

“And just how do you know that?”

“Maybe it would be best if we let Sasha explain,” Dad said, taking the bong from Mom.

Sasha sat down in a wingback chair and started talking.

CHAPTER NINE

The Magician Reversed

plans are poorly constructed

The room was silent, with only the occasional shout from the street downstairs breaking the quiet. I was twitching and about ready to scream when my mother poured a glass of wine and handed it to Sasha. He took a drink, gave her a smile, and she patted his shoulder. “Go ahead, Sasha. Tell him the truth.”

Sasha gave me a shy smile. “It started when my mother died,” he said, taking another sip of his wine. He flicked his eyes over to my mother, and she just nodded. He seemed to draw some strength from her, and something seemed to pass between them, but that could have been my imagination. “Five years ago. We live in Moscow. We never knew father. She always say he die before we born but would have loved us very very much. She teach ballet. In her day she prima ballerina with Bolshoi, but she injure knee and not able to dance anymore.” He smiled sadly, remembering. “Apartment filled with posters of her. She was quite beautiful. Strict but beautiful—she tough, but always knew she loved us. She good mother.”

“I’m sure she was,” Mom said, sitting down on the arm of the couch and stroking his arm. She pushed a stray strand of hair out of her face and smiled at him. “I’m sure she loved you all very much.”

“We all three big boys.” Sasha gave me a rueful look, and that shy smile again. “But clumsy. She say she never understand how she could have such clumsy boys. But she want us to have good life. In Russia,” he paused, “under old Soviet system the only way was sports or ballet. We too clumsy and big for ballet, she decide, so she decide we be in sports. She take us all the time to sports camps, to see if we could be Olympic athletes for Soviet. We wind up in wrestling camp. We naturals, coach say, and trainable.”

“I was a wrestler,” I said, without thinking. Colin slipped his hand into mine and squeezed it. I gave him a half smile.

Sasha smiled at me. “You have body for it, I think. Very nice body, compact and strong.”

“Thanks.” I had been a good wrestler, until I’d given it up my senior year. I got into wrestling because it was a socially acceptable way to roll around with another guy. Once I discovered the joy and easy accessibility of gay sex, I didn’t need it anymore.

“So we train all time, go to school, far from home. Camp was in what now St. Petersburg. We not see her much, but all the time she write letters. Every day, she write letters. She tell us to work hard, do our best, and she proud of us. We exercise; we train hard; they give us shots to make us bigger and stronger. We get better and bigger all time. Then system collapse. No more money from Soviet. Some wrestlers go back to families. It hard for Mother to keep us in camp. She have hard time keeping students too. Terrible times, lots of troubles, no money. But she manage to keep us in camp. We keep train. We get bigger.” He pointed to his chest. “Get big, like now. We all identical, look same, built same.” He smiled. “Coach used to never know which was which. We play tricks on him, tricks on other wrestlers. We compete, but,” he fumbled for words, “never good enough. We never make international team. Coach tell Mother put us in army; we better off there, never win Olympic medal. Then Mother get cancer.” His face clouded. “Was terrible time. She dying, worry about what happen to us. So join army. Army makes us wrestlers again. Not much different as army wrestler than Soviet wrestler. Give us shots. Make us lift weights. We get bigger and bigger. Then she die.” His eyes filled with tears, which he wiped away.

“I’m so sorry.” Mom rubbed his arm again. “That had to be hard on all three of you.”

“That when things change, when Pasha and Misha change.” He gave a bitter laugh. “That when we find out Father not dead, still alive.” He rubbed his eyes. “Father live in America. W

e find old letters. Life in Russia now bad. Barely enough money to eat. Had to have other family move into Moscow apartment, share with us, eight of us then in three-room apartment. Not enough heat. Not enough room. Terrible, terrible. Misha get idea to write Father ask for money. He rich American, Misha say. Maybe come to America, have new life for us. In America with Father. Me, not think such good idea.” He sighed. “Mother always make sure we learn English. We never know why. Now we know. Misha say she have us learn so we can someday go live with Father, so he be proud of us. I tell Misha bad idea. If Mother wanted us to go to America why she never say? Why she say Father dead? But he not listen. Misha determined. So he write letter. Months go by, no answer. Misha work in information at army, so he start finding out on In-ter-net.” He pronounced the word carefully, pausing between each syllable. “He find out Father have wife, other family. He say wife maybe not like that Father have sons in Russia, maybe Father not want her to know, that why he not answer letter. He say maybe Father pay us to not tell her.”

“Blackmail,” Colin interrupted. “Sasha, that’s a crime in America.”

“I tell him bad idea. If Father not want us, so be it. He forgot about us all these years, why things change now? But Misha not listen. Misha think he should pay.” Sasha shrugged. “So, he write again. No answer. Then he decide that if Father not want to help us he write wife.”

“I don’t understand,” I interrupted. It was a sad story, but what did this have to do with anything?

“Tell them, Sasha,” Mom said, giving me a look that made me close my mouth. I hadn’t seen that look in years. “Tell them who your father is.”

Sasha wouldn’t look at me. “Father name George Diderot.”

“What?” My jaw dropped. I looked at my mother, then to Sasha, over to my father, who just shook his head sadly. My head started spinning. “Papa Diderot is your father?”

No one denied it. I closed my eyes and tried to wrap my mind around it. It just didn’t compute. It didn’t make any sense. That would make Sasha, Misha, and Pasha my mother’s younger brothers—and my uncles. I felt sick. “I don’t believe this. It can’t be true—it can’t.” Papa Diderot, that fine upstanding Uptown gentleman who believed in good, conservative family values, was nothing more than an adulterer with three bastard sons from a Russian ballerina?

Hell was surely freezing over.

“Scotty, it’s true. I know it’s a lot to take in, but it is true,” Mom said. She got up and walked over to me, kneeling down right in front of me, taking my hands into hers. “It was a shock to me, too. But we”—she inhaled sharply—“had DNA tests done. Sasha and I have the same father. And if Sasha is my brother, then Misha and Pasha are too.”

“Why am I just now finding this out?” I exploded. “How long have you known? Why didn’t anyone tell me . . .” My voice trailed off, my anger starting to be replaced by something even worse. I remembered that first time I’d seen Sasha at Oz, the powerful attraction I’d felt for him, and my stomach began to churn.

The only reason I hadn’t slept with him, hit on him, was that he hadn’t been interested.

I had come this close to having sex with my uncle.

I wanted to throw up, to get up and run out of the room, down the back stairs and out of the house, screaming all the way. This was too much to be borne . . . this couldn’t be true . . . the one constant in my life had always been the family, and now . . .

“Scotty, you have to listen to me,” Mom was saying. “We didn’t want to tell you because we wanted the whole thing resolved before we said anything.” She swallowed. “I know, it was wrong, we should have told you, but I didn’t want you to be upset—”

“Does Papa Diderot know?” I choked the words out. I pictured him sitting at the dinner table, smug and fat and complacent, lecturing me on how I needed to go back to school, make something out of myself, and all the time he . . .

“It’s complicated,” Dad said, from the other side of the room. I turned my head and looked over at him. His face was grim, his lips compressed into a straight line.

“Misha wrote Maman Diderot.” Mom sighed. She got up and walked over to the mantel, where she picked up my senior picture, looked at it for a moment, then set it back down and turned back to me. “When she got the letter, she called me in hysterics. I had no idea what was going on. She wasn’t making any sense. She was just screaming and crying and I’d never heard her like that before. You know how she is, Scotty, always calm and quiet and gracious and never raising her voice. She was breaking things and screaming—I could hear things crashing in the background—and I had to go over there. This was three years ago. She was crazed, Scotty. I’d never seen her like this before. She was completely out of control. She’d just, I don’t know, snapped. I didn’t know what she was going to do. I tried to talk her down. I was afraid to leave her alone, even for a minute. She was threatening to kill herself, to kill Papa.... You remember when she went away for a few months?”

“I thought she—” I stopped. “You told us she went to visit a sick friend in Florida.” I hadn’t given it a second thought when Mom had casually told me over dinner one night, while spooning stir-fried vegetables out of her wok. Maman Diderot was always doing that kind of thing; that was the kind of thing ladies of her generation did. If a friend needs you, you go for as long as it takes. “You lied to me. You lied to me about it.”

“Yes, Scotty, I did, and I’m sorry about that. You have no idea how sorry I am.” She hugged me, getting gold paint and glitter all over her T-shirt. “I didn’t want to—it was a strange situation, and I didn’t know what to do.” She shook her head. “I didn’t handle it well. Hell, apparently I haven’t handled any of this well.”

I resisted the urge to push her away. “So where did she really go?” I said, in a quiet monotone. I wanted to scream. All of my life my parents had been so big on truth. And she’d lied to me. They’d both lied to me.

I could hear her telling me when I was a little boy, “Always remember, Scotty, that the truth shall set you free.”

Yeah, right.

“She went—” she took a deep breath and her eyes shone—“she had a bit of a breakdown, Scotty, and I thought it was better if she stayed in a convalescent hospital for a while and got the help she needed.” She stood up and picked up the bong, inhaling the smoke deeply. “I made some mistakes, Scotty. I didn’t know what to do. I was furious—furious—at my father. How could he have cheated on her, had children with another woman, and never told her, never acknowledged them, just abandoned them to their fate that way? What kind of parent does that, can do that? It was like he was a complete stranger to me. And at the same time I wasn’t sure, you know? I didn’t know these guys were my brothers. Maybe it was all just an attempt to get money out of us.”

“So what did you tell him?” Colin tried to put his arm around me, but I shook him off. I wasn’t in the mood for being comforted.

She bit her lip. “I didn’t tell him anything. I wanted to find out for myself. So, I wrote to Misha, asking for proof that he was who he said he was. At that time, I only thought, you know, that there was only one.” She tugged on her long braid and laughed. “I probably would have been right there with Maman at St. Rose’s if I’d known there were three. He never mentioned in the letter to Maman that there were triplets. He sent me letters from Papa to his mother—love letters—but that was just proof of an affair, not of parentage.” She took another hit, holding it in, then blowing it out in a plume slowly toward the ceiling. “The times made sense. I checked it out, you know? Put on my Nancy Drew hat and started sleuthing. I remember that my parents separated—”

“What?”

“You were a little boy; you don’t remember.” She shrugged. “Storm and Rain remember. They separated for a few months. I never knew the reason they separated was that he was having an affair. Maman never told me that. All she would ever say was he needed to sort some things out, and when he did, he’d come home. That’s all. Turns ou

t when the Bolshoi performed here—you know he’s on the ballet board—he met Svetlana at a reception, and that was how it started. He followed her around the country on their tour—I gathered that from his letters—but when the Bolshoi went back to Russia, he came home, begged Maman for forgiveness, and she took him back. And that was the end of it.” She reloaded the bong and took another massive hit. “They got back together. I never knew there was another woman until Maman showed me Misha’s letter. Then it all came spilling out of her. She was like a crazy woman. I really thought she was going to harm herself, so I called Dr. Langdon and he came over and sedated her. Papa was out of town then—he was in New York—so I called him and told him Maman was going away for a while.”

“You had her committed.” It was like she was a completely different person from the mother I’d always known.

She ignored that. “And when she came back out, I told her that”—she bit her lip—“I told her the story wasn’t credible. I figured I could buy Misha off, you know? I sent him money and asked him to stay away from us.” She waved her hands. “You know we have more money than we’ll ever spend. I told Misha I would send him a check every month as long as my mother was alive, as long as he never contacted her or Papa ever again.” Her eyes filled with tears. “Oh, Scotty, you have no idea how much I hated myself. I was no better than Papa, you know? I was buying them off. But I didn’t know how Maman would ever be able to handle it, you know? But lies are always, always, a mistake.”

“We thought it was all settled,” Dad said. “But what we didn’t know was that Maman was writing him too, and also sending him money.”

“And you had no idea this was going on?” I turned my attention to Sasha. Colin was squeezing my leg, and I shoved his hand away. I didn’t want to be touched. I know he was just trying to be there for me, and be a comfort, but I just wasn’t in the mood. “Your brother was soaking my mother and my grandmother and you had no idea?”

Mardi Gras Mambo

Mardi Gras Mambo